Wishful Thinking?

My wife and I recently attended our fiftieth college class reunion at the University of California Santa Barbara. Alums joined reunions of the physics department, the school paper, El Gaucho, forums on student activism in the 60s, fraternity and sorority gatherings, and student government types, reliving what was important to them in their youth during the tumultuous late 1960s.

I attended my class reunion gatherings and talked to some people I had only tangential connections with during my school years. OK, it was interesting, but for me, the annual football alumni reunion, held at the same time, was what really resonated. These old guys were my teammates, some older whom I looked up to as a rookie footballer playing for the Gauchos. The memories and relationships developed while being a member of a college football team far outweighed fraternity parties, lectures in the five-hundred-seat Campbell Hall, or times spent late at night in the library trying to stay awake prepping for final exams or being distracted by so many lovely coeds cramming at nearby tables.

If you ask any former college football player what were the highlighted experiences that stick in their memories of their college years, I will bet you that they will bring up their time on the football field, both in practices and games. Not only that, but they’ll be stories about the various personalities associated with the team, players, coaches, trainers, and even locker room attendants.

I wanted to play football from an early age because my father told me stories of his time as a football player, both in high school and at Vanderbilt, where his line coach was an all-American and a cousin. I wanted to have the same experiences as my father, so I joined the JV football team in ninth grade. Four years later, I entered UCSB as a freshman and played frosh football under Dave Gorrie, the head baseball coach and a storied athlete for the Gauchos in his day in both sports.

I was never a starter and spent most of my time scrimmaging against the first-string players, but I was able to make the varsity team my last three years of college. My only claim to fame and the way I was able to letter was as a long snap specialist. I could usually get the ball back to Dave Chapple, our all-American punter/place kicker, in an accurate and rapid manner, so I got to play whenever it was fourth and long, we scored, and it was time for a PAT, or when Dave attempted a field goal, which he usually made.

Of the three players drafted in the pros from our team my senior year, Dave Chapple was the only one to have a successful pro career, playing for a decade, setting long-standing records as a punter, and making the Pro Bowl. Today he is a successful nature artist.

My time as a player led to a desire to coach football after graduation, also true of a fair number of other former Gaucho players. I earned my teaching credential and enjoyed years of coaching high school and community college footballers, mostly for the US schools next to the Panama Canal. Fall was always the most exciting time of the year because it was football season. My experience as a member of a college team certainly helped when I took up my coaching duties.

Now I’m retired, long out of coaching, and barely keep up with what football is available on my TV. Why am I now so interested in the extinct football programs in the state? I think it is because the program I so enjoyed as a student was canceled three years after I graduated. If I wanted to follow my school’s team, I could not. Football was brought back as a club team in the 1980s largely because of the efforts of two students and a couple of alums who missed football at their college. The two alums, Stoney and Puailoa, both local high school coaches and former football stars at UCSB, got some of us to donate small sums to get the club program off the ground. I did my student coaching under these two coaches at a local high school near my university. I sent twenty-five dollars, which for me, with a large family to support on a teaching salary, was what I thought was reasonable. The program was revived, and after a couple of failed attempts, the students voted to fund a Division III non-scholarship program coached by Mike Warren (Mike, our captain, frat brother, and rugby player, recently passed away.), a former teammate. Eventually, the football team, without providing scholarships, was doing so well it moved up to NCAA Division II. Then disaster struck for a second time.

Like the first time football was dropped by the university in 1972, NCAA rules required that if all the other sports programs were Division I, then football must also be Division I, which means lots of scholarships and more expense, not only to fund a very expensive football program but to match the funding for additional women’s programs mandated by Title IX. A vote was held by the students to raise fees, and, as in the seventies, it failed, and football was canceled for a second time.

So here I am going to football reunions with guys in their seventies, reliving the glory days, but not able to be a fan of a current Gaucho football team. I could follow their baseball or basketball, but it just isn’t the same. I got to thinking, what if all the expense and rules of NCAA programs and Title IX parity with women’s sports could be avoided. How could this be done? UCSB and other universities in California have viable club sports teams that are not under NCAA, Title IX, or NAIA rules. They are largely student-run and student-funded, yet some of the programs are the equivalent of varsity sports that are NCAA in other universities.

I played on the Gaucho rugby club as a student and loved the experience. We had a volunteer coach who was also a player. Rod Sears, who had played his football under our coach at Stanford, was our quarterback coach during football season and our rugby coach during rugby season. We players lined the fields ourselves for home matches and drove our own cars to away matches. Very little money was involved on the part of the university. It was glorious fun. Today UCSB is still playing big-time university rugby as a club team and a few years back played in the national finals, losing to Davenport in the championship match at Stanford in 2011. Still, a fall without a UCSB football schedule is sad to me.

I dabbled a few times with lacrosse club practices that some guys from back East started up when I was in graduate school during my first year of marriage. I even got to play in one match against UCLA, but just for a couple of minutes, as I had quit going to practices to focus on work and student teaching. Now lacrosse has become a very popular sport in California, where it once was exclusively an East Coast sport. Most universities in California that play lacrosse do so as clubs and not as NCAA or NAIA varsity programs. The club conferences are equivalent to programs at the NCAA level in other parts of the nation.

Crew is a long-standing club sport at my university and also across the nation, providing opportunities for college athletes to compete at high levels, though without scholarships or NCAA sanctioning. In each of these major sports, there are national associations that recognize national rankings and even all-American status. UCSB plays rugby in division IA of the California Conference. The Gauchos compete in lacrosse in the West Coast Lacrosse League of the Men’s Collegiate Lacrosse Association. Their website indicates it provides “virtual varsity” lacrosse for schools without varsity-sanctioned programs. The crew team competes in the American Collegiate Rowing Association against other club teams not part of the NCAA.

Back East, there is a viable club football association with twenty-six college football programs that compete as student-run football clubs. It’s called the National Club Football Association and is divided into four geographic conferences. Wikipedia lists thirty-seven collegiate club football teams, all in the East. A few are at universities that field major varsity programs, as well. Why couldn’t UCSB add football to its club programs?

It seems unlikely that my college will ever again have a major varsity program in football. It is too expensive. There is no university funding. Starting an NCAA-recognized program in football would require at least 65 scholarships which would have to be matched with new women’s programs. Students are unlikely to pick up the tab by voting for higher fees just so they can watch the local team struggle to compete against established programs. They failed to do so twice before.

So why not give former high school and community college players attending the university who still have it in them to want to play their favorite sport a chance to play in a less expensive student-run club program with no scholarships, just as those teams in the East are doing?

Here’s the rub. If UCSB were to start up a club team, there would be nobody to play. There are no college club football teams in California, and traveling thousands of miles to play teams out of state makes it impossible to fund such a club team. For my school to have any chance at returning to football, it would have to have other nearby club teams to play.

This got me thinking. I researched how many former football programs were canceled, some were teams I played against in my day, and thought that if just a few were to start viable club teams, it would make it worthwhile for my college to do the same. I figure it would take at least four schools to start programs to make a semi-interesting season of competition.

Schools such as Santa Clara, Long Beach, and Fullerton have had nascent movements for a return to football, as has UCSB, but expenses always get in the way, as well as unrealistic ideas of joining the big time. A club system, if it got started in conjunction with other schools, might allow for those who enjoy the game for its own sake to continue playing in their home state while pursuing their educations.

Club football would not have the status of big-time football. It would have to overcome resistance from students who only see big-time competition as something worthwhile to support. There would be issues with the various recreation departments over practice facilities, equipment, insurance, and so forth, but if schools can do it in the East, why not in a California that once supported twenty-six programs that are now gone for various reasons?

Just as club rugby, lacrosse, crew, sailing, ultimate frisbee, and a variety of other sports have taken off outside the athletic departments and NCAA establishment, why not club football?

I have dreams of someday seeing my school fielding a team and playing against other former rivals, just as we did so many decades ago, and doing it just as we did on our university’s fledgling rugby club, crew, and later the lacrosse club.

This is how I got thinking about the history of former football programs and became curious about why they were canceled and what their past glories might have been. I can imagine scores of football alumni teaming up with interested students to promote a conference in our state made up of viable club teams. I even imagined schedules based on geography to reduce travel time and expense.

A pipe dream, I know. But why not write about it and perhaps stimulate enough interest to see that future high school and junior college players have the same opportunities that my contemporaries and I had years ago to play the sport we enjoyed so much in our home state during our college years?

Fourth and Twenty-five: The Sad Demise of More than Half of California’s Collegiate Football Programs. Can They be Resurrected?

On the tenth of November of 2018, Interim Head Coach Damaro Wheeler led his squad of Lumberjack football players onto Simon Frazier University’s Terry Fox Field. The Humboldt State players most likely passed the statue of the Canadian university’s most famous alumnus, Terry Fox, a former JV basketball player for the SFU Clan. Their mascot is a Scottish terrier named McFogg the Dog.

Wheeler may have wondered why a former JV basketball player is remembered by having a stadium named after him and his image shown in a life-size bronze statue in running form placed at the entrance. If anyone thought to ask, they would have learned Fox became famous after having his leg amputated due to cancer. He continued to compete in wheelchair athletics and learned to run distance with his prosthetic leg, depicted in the statue. He is most famous for his attempt to raise money for cancer research by running the length of Canada from the Atlantic Coast to the Pacific. He raised a significant amount of money, his difficult journey was followed by the media, and crowds of thousands cheered him on, admiring his fortitude. He failed in his attempt to complete the task, dying of his cancer.

Wheeler might have thought Humboldt State needed a person with the fortitude of Fox to raise money for his football program in Arcata. It too was dying after Herculean attempts by the local community to raise funds to keep the ninety-year-old program going. Wheeler’s team was playing in its last football game.

Wheeler made a little bit of history himself. He became the first African-American head football coach for Humboldt State. The previous spring, Cory White was designated the prior interim head coach after Humboldt State’s most successful coach, Rob Smith, resigned during an acrimonious dispute with the university’s administration. White, who had been the offensive line coach and a Lumberjack football alumnus, left after accepting a job back at the University of San Diego where he’d worked a couple of years before. He must have considered his options and chose a secure job over one with doubtful longevity.

Wheeler was given the task of keeping the program going one more season. He had been the defensive back coach the previous season, and before that worked with a number of programs from Mission Bay High School in his hometown of San Diego, to UC Davis, Central Washington, Southern Oregon, and most recently the nearby Redwoods Junior College. Soon he’d be looking for another job. Now Wheeler was finishing his first season as a head coach navigating a team on the verge of extinction.

The team picture I found online showed nearly eighty players, though not all flew to Vancouver and bussed north the twelve miles to Bunaby Mountain, British Columbia for the game. The team bios indicated the players came almost exclusively from California cities and towns from San Diego all the way to Arcata. They were representative of the ethnic diversity of the state.

It had not been a great season. The only win so far had been a close 23-16 win against this same Canadian team back in Arcata at HSU’s home field, the Redwood Bowl. Simon Frazier is the only Canadian university that competes with U.S. collegiate teams in the NCAA, and they played American style football rather than by Canadian rules. They had only one win in 2018, crushing Willamette, a DIII school, and no wins in the DII Great Northwest Athletic Conference. Humboldt State, the farthest north of the California State Universities, joined Azusa Pacific University, an associate member of the GNAC, as the only two remaining Division II football programs left in the state. The rest of the GNAC teams were in Washington or Oregon with the exception of this one lone British Columbian squad.

The previous week the Lumberjacks lost for the second time to Azusa Pacific’s Cougars in HSU’s last home game in the Redwood Bowl. Wheeler may have had mixed feelings about those loses. He played his collegiate football for the Cougars fifteen years before. The game went into overtime after starting quarterback, Joey Sweeney (not a relative that I am aware of), long haired, bearded, six three, 225-pound junior kinesiology major from the Central California town of Oakley on the San Joaquin River, suffered from an injury. In his team picture he doesn’t look happy. Could he have been sad that there would be no football for him to play his senior year? Redshirt freshman Andrew Tingstad, a tall, thin backup quarterback from Washington, took over for Sweeney, only to also be injured and replaced by third string senior QB, Brenden Davis. Davis was from Newman, California, a small central valley town in Stanislaus County near Modesto. He played previously at Clarion University in Pennsylvania and for Cabrillo College near Santa Cruz.

Davis led the team from late in the third quarter. A thirty-seven-yard field goal by Jose Morales led to a seventeen-seventeen tie at the end of the fourth quarter resulting in an overtime period. An intentional grounding penalty and a missed thirty- seven-yard field goal attempt by Morales enabled the Cougars to pull off a drive into Lumberjack territory and finish the game with a field goal and a 20-17 win; a sad, but exciting finish for the last home game for the HSU team fans.

The following week the Lumberjacks ran onto Terry Fox Field on a cool forty-nine-degree afternoon. The green field was surrounded by trees, the fall having left them bare. Modern college buildings loomed behind the stadium. Just 648 fans sat on the temporary stands or on the grassy hill overlooking the field. Most of the Lumberjack games played at home usually had between four and five thousand fans attending the games, nearly filling the 6,000 capacity stands, except for the poorly attended second Central Washington game. CWU had crushed the Lumberjacks in the previous away game.The kickoff began at one. Davis took the first HSU snap from center, his first start as a QB for HSU.

The Lumberjacks scored first after Davis led the team on a sixty-yard drive into Clan territory. Jose Morales, a six-four, 240-pound senior from Lompoc, who looks more like a defensive tackle than a kicking specialist, lined up to kick a thirty-eight yard field goal. His online team picture shows a smiling face with a goatee. He was a senior and a grad of Alan Hancock College in Santa Maria with lots of previous football success, so perhaps playing in his last season didn’t have the same sting as it did for the injured junior quarterback, Sweeney.

The second quarter didn’t go so well for the Lumberjacks. The Clan scored on an intercepted pass runback and a field goal, ending the half ahead at 10-3. The Lumberjacks roared back after the halftime intermission, putting a limping Sweeney back under center, to score on a nineteen-yard pass to Colby Stevens, a junior wideout receiver from Camarillo, set up by a fumble forced by junior linebacker, Isiah Sires-Wils of Willow Glen High School in San Jose. Sires-Wils’s team photo shows a frowning young man, perhaps also contemplating his senior year without football. This score followed by a thirty-nine-yard field goal by Morales put the Lumberjacks ahead thirteen to ten. The Clan came back on a seventy-nine-yard drive to go ahead sixteen to thirteen after a failed extra point attempt. A forty-yard field goal by Morales tied up the game at sixteen each.

In the fourth quarter the injured Sweeney led the Lumberjacks on their own seventy-nine-yard drive ending in a five yard score by senior running back, Tyree Marzetta of Hunter’s Point, San Francisco. Hunter’s Point is famous as a former naval shipyard, current location of public housing, and fears of residual radioactive contamination, though the views of the Bay are magnificent. Marzetta’s team photo shows a scowling young man, with a goatee and short dreadlocks. Marzetta’s score and Morales’s successful extra point, the last for Morales and for all time for the North Coast gridders, allowed the visitors to hold on to the lead during the last three minutes of the game, and end HSU’s ninety seasons of football with a memorable win.

I wonder, on the flight home, what the coaches and players were thinking. The exciting win allowed them to stay out of the GNAC cellar, just above the hapless Clan, but for the underclassmen knowing the university failed in their attempts to continue the long-standing program must have weighed heavily on their minds. Would they stay on to finish their degrees at HSU or attempt to transfer to other schools to play out the last years of their eligibility; could they maintain their scholarships? I would imagine for some it was hard to keep back the tears.

The various assistant coaches, many relatively new to HSU, were now out of jobs. Coach Wheeler was eventually hired as an assistant for the South Dakota School of Mines Hardrockers, a far cry from the beaches and warm climate of his hometown in San Diego.

The GNAC was left with only four football teams for the 2019 season, spread in three West Coast states and one Canadian province from Southern California to British Colombia. Though they played each other home and home each season, they had to find additional teams to play to fill out their schedules from other DII schools. A look at previous schedules showed they sought games against teams in Texas, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, South Dakota, Idaho, Michigan, and Missouri, where DII football programs thrive. Having to add additional games in distant states adds to the financial stress already facing the remaining football programs on the West Coast. Travel by plane is expensive. This helped push other programs beyond being affordable, such as previously powerful Chico State. The survival of West Coast DII football in the GNAC remains questionable.

What led up to the decision to cancel a viable football program that began in 1924? The university had been struggling with budget deficits and looked for areas to cut to lower expenses by nine million dollars and achieve a balanced budget by 2020-2021. The athletic department needed 750 thousand dollars to make up for large deficits. Football, which cost a yearly one million dollars, was the most expensive of the twelve varsity programs, so after the 2017 season President Lisa Rossbacher announced that unless the local community could come up with a commitment of half a million dollars in yearly donations to the athletic department, she would have to cut the Lumberjack football program.

The community, led by local business leaders and football boosters, stepped up to the challenge and saved the program from cancellation raising more than 500,000 dollars that first year. President Lisa Rossbacher announced the program was saved. This did not save long time veteran Head Coach Rob Smith from resigning. The turmoil over the cuts and doubts about the future of the program resulted in a rancorous dispute between Interim Athletic Director Duncan Robins and Smith, played out in public statements, letters, and TV interviews. Smith felt disrespected after building a successful program during his ten-year tenure as head coach. His last season with the team resulted in a national ranking in the top twenty DII schools. In order to be a viable program, off season recruiting is vital. Smith felt without a clear picture of the future and money to travel to recruit players his staff was being put in a precarious situation. He decided to resign.

As we have seen above, the transition after the last-minute rescue of the program did not go smoothly. The fund raising continued for the following season but fell short, raising 329,000 dollars, not enough to satisfy the school administration’s demands.

In July of 2018 Rossbacher approached the podium and took the mike. “Our football team has been an important source of pride for our students, staff, and alumni, as well as our regional community. Sadly, and despite a tremendous fund drive effort, we found that football cannot be sustained through student fees and community giving. At the same time, the University cannot continue to subsidize budget deficits in Athletics without threatening our academic programs.” The 2018 season would be HSU’s last.

Humboldt State was one of the latest football programs to fall victim to the chopping block. More recently the athletic director of Azusa-Pacific University (Where I did a master’s degree in education with a PE emphasis while starting my coaching career in nearby Arcadia High School) announced that as of December 2020 the Cougar football program would be cancelled. This ended the last Division II football program in California. California has lost more than twenty-four of its former collegiate football programs. The reasons are various, but budget concerns and NCAA rules appear to be the primary cause. The vast majority of cancelled programs were cut since 1972.

Why is this a significant date? In 1972 Richard Nixon signed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity Education Act in the wake of Women’s Liberation Movement. Prior to this legislation few collegiate athletic programs for women existed. Women’s sports were governed by the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, established in 1971 to offer leadership for the growing interest in sports by America’s coeds. Part of the 1972 legislation that sought equality in education for women included Title IX, which sought to ensure a more equal distribution of funds for women’s sports programs, including scholarships offered to student athletes.

This presented a challenge to collegiate athletic departments. To comply with the rules, as interpreted by the Department of Education and the NCAA, schools had to move toward offering more women’s sports, fund them more equitably, and offer similar numbers of scholarships for both sexes.

Sports can be expensive, particularly at the Division I and II levels that offer scholarships, or at NAIA schools offering athletic scholarships. Students are not always willing to pay higher fees to support additional sports programs. Administrations stress over budgets, and alumni cannot always be counted on to donate the funds needed to comply with the new rules.

The options for athletic programs to comply with interpretations of the Title IX provisions were to add women’s sports, eliminate some men’s sports, or a combination of both. Fortunately for women the trend has been generally to add additional women’s programs. This has been a boon for female athletes, as their participation and the number of well-funded programs has grown tremendously over the last several decades. The opposite has happened to men’s sports. Many schools have reacted to Title IX by cutting nonrevenue earning men’s sports. Wrestling, cross country, indoor and outdoor track, tennis, golf, and swimming have suffered as a result. Then there’s football.

Football is primarily an all-male sport, though occasionally young women join the teams, but it is rare enough that it makes the news. Football requires large numbers of participants. The only women’s sports that come close are crew, rugby, and soccer, but major men’s football programs carry upwards of eighty players. Under NCAA rules major programs are required to offer at least sixty-five and up to eighty-five scholarships. To try to equate this to women’s programs would require both dropping some men’s programs and adding more women’s sports. In addition travel, equipment, and coaching expenses are far higher in a football program than in women’s basketball, soccer, or even track. This is not the only reason California has dropped so many football programs over the last several decades, but it has had an influence. The issue remains controversial. Some schools have dealt with it without dropping football while others have decided they cannot support such an expensive sport. Though football is usually the best earner in revenue for the athletic department, only the biggest division one programs, which are on TV each week, have gigantic stadiums that fill up to overflowing, and sell tee shirts and fan trinkets by the ton, as well as receive donations from well-to-do alumni, make profits that can be funneled back into the program and to support non-revenue earning sports, as well as excellent women’s programs. Most football programs need additional funding beyond what is earned during the season.

Part of the funding issue is due to NCAA regulations. In order to compete in a Division I or II conference, schools have to offer a certain amount of scholarships regulated by NCAA rules. They are not allowed to compete in different divisions in different sports. For example, to be DII Humboldt had to offer at least ten DII sports, with their allotted scholarships. They could not decide to compete in DIII in football and DI in track and still be considered a DII school. This means that some schools that cannot afford the scholarships required to be competitive in DII or DI football and the accompanying equivalent in women’s programs had to drop their football programs in order to keep the other programs at a DII level. This happened twice at the school where I played football.

The irony for California is that according to the National Football Foundation, despite the loss of many former football teams, the net number of collegiate programs continues to grow, with new teams being added or revived each year, so that there are more football programs now than ever before. In 2018 there were 778 college football programs in the NCAA and NAIA in all divisions. In the six years prior to 2018 thirty-five institutions had added football. Seven in just 2018 and five more plan to add football in 2019. Most of these new programs are found in the Midwest and South, with a few in the Western States and the Northeast, but none in California, except at tiny Lincoln College in Oakland, that started their athletic program in 2021. What is wrong with California? These institutions must find value in what football brings to their students and community; at least enough to fund what is often a very expensive proposition. But it adds excitement to the beginning of the school year, unites students around a common activity, and then there are the marching bands, cheerleaders, alumni interest, publicity, recruiting tool for potential students, and so forth.

California has 646 high school football programs and sixty-nine junior college teams. There are thousands of young men and perhaps a few women who graduate from their schools each year and some may want to continue playing football at a four-year school in their home state. California currently has just twenty college football programs. Eleven are DI schools. Stanford, Cal Berkeley, USC, and UCLA play as part of the Football Bowl Subdivision. This division has strict requirements under NCAA rules for a large number of full scholarships for football players and for those in other sports, as well as requirements for attendance at home games. These programs are extremely expensive and often the head football coach has the highest salary of anyone associated not only with the university, but if in the public system, in the state government.

Sacramento State, San Jose State, Fresno State, San Diego State, University of San Diego, UC Davis, and Cal Poly San Luis Obispo are in the DI Football Championship Subdivision. These schools are eligible for the postseason playoffs to determine the national championship, sanctioned by the NCAA. They have different rules than the FBS in regards to scholarships and how they can be divided up.

Azusa Pacific University was the only DII football team left in California. The Cougars were co-champs with Central Washington in 2018 and got a bid to the DII national playoffs, representing the GNAC. Now there are no schools in California representing NCAA DII football.

California has eight DIII programs, Occidental College, Harvey Mudd-Claremont-Scripps, Pomona-Pitzer, Redlands, La Verne, Chapman, Whittier, and Cal Lutheran. All these schools are within driving distance from each other in Southern California in the Greater LA Region. Harvey Mudd-Claremont-Scripps made the 2018 DIII national playoffs, but like Azusa Pacific, got crushed in the first round. The new program at Lincoln has applied to join the NCAA and has been playing the smaller colleges in the Northwest and Southwest, as there are no DIII or NAIA football programs in Northern California.

There are no NAIA football programs left in the state. Menlo College dropped their NAIA football program in 2015, citing travel expenses as a key issue as there were no nearby NAIA teams to compete with.

If a football player wants to play in California after graduating from high school or community college, he had better be able to make a big-time team, which means competing with scholarship athletes, the best from not only California but the rest of the nation, even the rest of the world. If the ballplayer cannot rise to this level, then he or his parents had better have enough money to send him to one of the expensive private colleges that offer DIII no scholarship competition. The only other option is to seek programs out of state.

When I was coming up as an average footballer after my senior year, I had lots of options of schools where I could play and even be recruited. I wasn’t all-anything, I just wanted to continue playing, as my dad had done in his day. I loved it. There were so many more programs back in the 1960’s, even some new ones that eventually did very well. Any decent footballer could find a spot on a team, enjoy one or more years of competition, brag to their children and later grandchildren, and perhaps do a bit of coaching after the experience. When I think of what it would be like if I graduated today, I doubt I would have been able to find a school in my state where I both wanted to go and where I could continue playing the sport I put so much time and effort into in high school. I find it sad, probably because the school where I played, which I would like to have been able to follow as an old alumnus, has dropped its program. Those were wonderful years for me. I would like for more young men to be able to enjoy the same experiences I had as a student. Something is gone from the spirit of a school when football is dropped. Soccer just doesn’t have the same influence on a school as a good football game in the fall.

I recently attended my fiftieth college graduation reunion. I knew just a few of my fellow graduates at the functions. I try to attend our football reunion each year. It is still going despite the lack of a football team on our campus. The football alums are among the most generous donors to our school’s athletic programs. Our coach’s son, who was our quarterback, reminded us of what his father, a prominent coach who had years of being a head coach at major programs, said about football. “You probably won’t remember who you sat next to in English, but you will certainly remember who you played with on your football team.” That certainly rings true. My father always enjoyed going back to his college reunions and especially reconnecting with his football buddies.

While at the last football reunion I had an interesting talk with a former player who became a college administrator about the complicated aspect of funding sports programs, especially football.

I propose in this project to delve into the history of the extinct football programs in our state. To find out why they were dropped, what interesting stories come out of their existence as football schools, and then offer a proposal for reestablishing a new type of football organization for the state that might allow for a less expensive, less highly regulated, more student-oriented program for those who just enjoy the game and want to play it during their college years, in their home state.

Below is a list of the cancelled programs in California and the approximate dates of either the cancellation or the last season played. I found varying results online. When a program died it was not always perfectly clear cut exactly when. Some dates indicate when the cancellation announcement was made, while others list the last season’s date. Some programs carried on briefly as clubs and some were cancelled when the schools merged with other institutions. Some programs were canceled and then brought back and were canceled again. I have listed the extinct teams in order of the dates the programs ended. There may be a few tiny bible colleges that once briefly fielded football teams and since have folded or been absorbed by other Christian colleges or no longer support athletic teams, but information on these is difficult to discover. Southern California College eventually became California Baptist University, now a DI school, but no longer sponsors a football program. US International University was previously known as Cal Western. It ran into financial problems and dropped its athletic programs and eventually merged with a for profit school, Alliant, which does not sponsor athletics.

Cal Baptist 1955 UCSB 1992 Cal State Northridge 2001

Pepperdine 1961 Long Beach State 1992 St. Mary’s University 2004

South California College 1962 Cal State East Bay 1993 Menlo College 2015

UCSD 1969 Cal State Fullerton 1993 Humboldt State 2019

University of San Francisco 1972 Santa Clara U. 1993 Azusa-Pacific 2021

Loyola Marymount 1973 Cal Tech 1993 UC Riverside 1976

San Francisco State 1995 LA State 1978 University of the Pacific 1996

US International U. 1980 Sonoma State 1997 Cal Poly Pomona 1983

Chico State 1997 Occidental 2020

Where Did All the Football Games Go in Southern California?

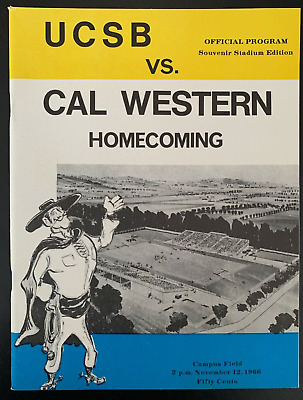

On a Saturday evening in 1966, when I was a sophomore at UC Santa Barbara, I drove my white stick shift, used Corvair Monza to the dorms, picked up a date I had met at an on-campus dance, and drove down the 101 to San Fernando Valley. It was only a couple of hours’ drive, and I wanted to watch our Gaucho football team play the San Fernando Valley State Matadors.

I was on the UCSB team but not on the traveling squad, so I was on my own getting to the game. I had been asked to redshirt. I told “Cactus” Jack Curtice, our famous head coach, that I was planning on graduating on time, if not earlier, so I passed on sitting out my sophomore year to avoid adding a year to my college education (in retrospect, I wonder if I should have redshirted, I only got in one game that season and stayed extra quarters to earn a teaching credential anyway). I had made the team during spring ball and survived the difficult two-a-day practices in late summer, but with several centers ahead of me, I was not needed for away games, so my role was on the scout team.

Valley State, now known as Cal State University, Northridge, was a relatively new college, only having become independent from what was Los Angeles State College in 1958 and establishing a non-scholarship football program in 1962. One of their few wins that first season was against the Gauchos.

By 1966 the school had about ten thousand students, equivalent to our school, but the football program was struggling with few scholarships. The game was played at Birmingham High School’s stadium in Van Nuys. It wasn’t until 1972 that the Matadors had their own on-campus venue, North Campus Stadium, built on what was an old harness racing track, Devonshire Downs.

The night game wasn’t all that competitive. My Gaucho team was up 31-0 by the third quarter, and we finished the game with a 31-12 win, likely the result of Coach Curtice allowing backup players a chance to get in the game in the final quarter. The 1966 Matadors went 2-7-1, tying Whittier College and beating Santa Clara and Occidental in close contests. Their final game against Los Angeles State’s Diablos (now CSU Los Angeles, no longer the Diablos, now the Golden Eagles) was a loss but drew 6,000 spectators to Birmingham’s stadium.

Valley State also played Cal Poly Pomona and Long Beach State, as did Santa Barbara. None of those teams exist today. Nearly all the Cal State University football programs in Southern California: CSU Northridge, CSULA, CSU Long Beach, Cal Poly Pomona, and CSU Fullerton, are no more, along with my UCSB Gauchos and the UC Riverside Highlanders, and a collection of private colleges, notably Loyola/Marymount, Cal Tech, Pepperdine, Occidental, Azusa-Pacific, and a few others. The only Southern California State University that still sponsors a football program is San Diego State. UC San Diego had a one-year shot at football, then folded as a club. Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo on the Central Coast still plays football.

Each of these universities once provided a home for college football players. Each had its ups and downs, but each also had its glory years before Title IX requirements, NCAA rules, and budget difficulties resulted in the cancellation of once-viable programs. I am going to attempt to highlight the “good years” of those football teams and discover why and when each program was eliminated. For this section, I’ll focus on CSU Northridge and UC Riverside.

Today CSU Northridge is one of the five largest universities in the United States, along with Fullerton, and Long Beach, that do not sponsor football. Since the program began in 1962, it gradually developed into a Division I NCAA competitor, playing the likes of Boise State, Utah, Fresno, Davis, San Jose State, San Diego State, Kansas State, and SMU.

The Matadors played UCSB eight times, beating the Gauchos in five contests between 1962 and 1971 when UCSB first canceled football. In 1962, Valley State’s first season, their victory over the Gauchos was one of three the new program managed, which included close victories over UC Riverside and LA State. The following year, they didn’t play the Gauchos, winning only two games against the UCR Highlanders and Redlands in close contests. They lost to three other California Collegiate Athletic Association football teams and three non-conference teams by substantial margins.

They played the Gauchos again in 1964, Coach Curtice’s second year as Gaucho mentor after leaving Stanford, and beat UCSB 7-0, beginning a string of four straight victories, followed by six straight losses in the remaining games. The two final losses versus California Collegiate Athletic Association opponents were by large margins against number six ranked (College Division) San Diego State and number two ranked LA State. Five thousand fans filled Monroe High School Stadium for that last game against LA. LA State went on to a perfect 9-0 season, 5-0 in the CCAA, and garnered a Pasadena Bowl victory over Slippery Rock College of Pennsylvania played in Pasadena’s famous Rose Bowl Stadium.

The 1965 season was a dismal one for Coach Winningham’s Matadors. They lost to the Gauchos in their first game, 20-0, won only one game the entire season, against Whittier, 14-12, and were crushed by San Diego, highly ranked Long Beach, and LA. LA went on to play UCSB in the Camelia Bowl for the Western Small College Championship. The Matadors were outscored 330 to 49 and were last in their conference and last again in 1966.

The 1967 season gave Coach Winningham’s boys something to yell ole` about. They went 6-4 and tied with Long Beach and Fresno with 3-2 marks in the CCAA. San Diego State was first in the CCAA and ranked number one among the nation’s small colleges, going to another Camelia Bowl in Sacramento, where they beat SF State 27-6. Because San Diego chose to battle San Francisco for national championship honors, Valley State was chosen to represent the CCAA in the Pasadena Bowl against West Texas State, then from the Missouri Valley Conference. Interestingly, Jack Curtice was the Buffalo head coach in 1940 at the beginning of his college coaching career. The Buffalos gored the Matadors 35-13. This was Valley States’ only bowl appearance.

When Valley State played the number one San Diego State Aztecs, the stands at Birmingham High School overflowed with a crowd of 9,200 rabid spectators. They were entertained with a rousingly close contest, with San Diego winning 30-21.

When the Valley boys played the Gauchos in our stadium earlier in the season, spectators experienced a similar exciting contest. I played in that game but have no memory of it. My role was as long snapper for punts, PATs, and field goals. When I found the score online was 28-27, I wondered if our record-breaking kicker, Dave Chapple, had missed an extra point to give the Matadors the victory. I looked up the article in the archives of our school newspaper, El Gaucho, and learned that Dave missed a 49-yard field goal when the ball bounced off the right goalpost and also missed one of his few unconverted PATs in his college career. I snapped to his holder in both of those plays, and I know I didn’t miss. The article says Dave suffered from an injured ankle during that game.

The Valley State QB, Bruce Lemmerman, led the Matadors back from a 21-7 deficit at the half to the one-point victory. Lemmerman was later drafted by the Atlanta Falcons. Dave Chapple went on to play pro football for the Rams, Buffalo, and New England, setting punting records and making the all-pro team. That day was not representative of what a marvelous athlete Dave was. Tom Broadhead played well as a running back and receiver that day for the Gauchos. Tom was drafted by New Orleans after his record-breaking year at UCSB. I have just learned he is home with his family, as I write this, in hospice care. He has been fighting cancer for ten years. You don’t forget your college teammates, and Tom and his wife have been receiving encouraging e-mails from former Gauchos prompted by one of our captains. (Tom passed away shortly thereafter.)

In 1968, the Matadors had another winning season, going 5-4, with all their wins coming in non-conference games, except their 21-20 victory over Long Beach. They both shared last place in the CCAA. The final game, a 42-27 loss, was against cross-town rival, LA, in front of 7,490 fans at Birmingham Stadium.

Santa Barbara met the Matadors again in 1969, dominating the game with Curtice’s son, Jimmy, at QB. The Gauchos won 26-2, with the Valley boys’ only score coming on a blocked punt that rolled out of the endzone. 6,000 fans watched the game in UCSB’s home stadium.

The CCAA had changed with Fresno, Long Beach, and LA moving into the University Division, being replaced by Cal Poly Pomona and UC Riverside. Northridge was still able to beat both Long Beach and LA by comfortable margins. Leon McLaughlin led the program to a 4-5 mark in his first year as head coach.

The Matadors played UCSB again in 1970 after UCSB moved up to the University Division, Curtice having left the head coach duties to his long-time offensive line assistant, Andy Everest. They downed the Gauchos 13-7. They beat Sacramento at home in Birmingham’s stadium 34-10 in front of five thousand fans. Hapless LA State was handed a 45-0 loss on the same field with 2,500 fans in the stands. The last game was a loss to Long Beach 21-0, with only 200 watching the game. It was Thanksgiving break. Two high school championships had been played the same day prior to the 49er-Matador faceoff, so the field was a muddy mess. This was a 4-6 season.

The Gauchos met the Matadors for the last time in 1971. Another win for the Valley team, 15-14, edging the Gauchos with a two-point conversion on a sloppy Devonshire Downs field. They went 4-7 under new head coach Rod Humenuik.

They went 6-5 in 1972. In 1973, under another new coach, Gary Torgeson, they went 2-9 and were last in the CCAA as a Division II NCAA program. The same mark repeated in 1974, though attendance at North Campus Stadium was respectable. The 1975 season improved marginally with a 4-7-1 tally. This was the year UC Riverside won the CCAA.

In 1976, Hall of Fame coach Jack Elway took over for three years. In the first season, he took them to an 8-3 record. The CCAA shrank to just three teams when UC Riverside dropped football after the previous season’s championship. The 1977 team went 7-3-1 and drew capacity crowds to North Campus Stadium. In Elway’s last season at CSUN, they went 5-5. He subsequently went on to coach at San Jose and Stanford.

Tom Keele took over in 1979, and the Matadors went 3-7. The following year, they went 5-6, and home attendance began to shrink. In 1981 they won the diminished CCAA and went 6-4-1. In 1982 they joined the Western Football Conference and set a 4-7 mark, taking third in the new five-team conference. 1983 was a banner year. They placed first in the WFC with an overall record of 6-4. Attendance at home alternated between several hundred to several thousand, depending on the success of the team in previous games. The following season, they slipped back into the cellar, winning just three games and losing seven, including losing to the three other teams in the WFC. 1985 was another 4-7 mediocre season.

Bob Burt took over in 1986 and took the Matadors to a 7-3 season and second place in the expanded WFC. The team was ranked as the number nine D-II team nationally. Attendance at home games increased, nearly filling the small stadium each homestand. The next year was another good one, taking second in the WFC behind third-ranked Portland State, with an overall record of 7-4. Home attendance remained strong. Burt managed winning seasons in 1988, 1989, and 1990. 1990 was a unique season. Cal Poly and CSU Northridge had identical 4-1 records in the WFC, and both qualified for the Division II NCAA playoffs. Over 7,000 fans crowded into North Campus Stadium to watch Cal Poly’s seventh-ranked team edge the 13th-ranked Matadors 6-3, the only conference game CSUN lost. They met again for the first round of D-II championship playoffs, and Cal Poly won again in a close game, 14-7. CSUN’s overall record for the season was 7-4.

After that stellar year, things did not go so well for Coach Burt. They went 3-7 in 1991 and 5-5 in 1992. The NCAA ruled that schools competing in D-I sports could not play D-II football. This became an economic challenge for CSUN, but a student referendum enabled some financial help as the program went to a D-I level. This same NCAA rule and a failed referendum to increase fees at UCSB ended our program for the second time. CSUN and several other colleges formed a new D-I conference, the American West Conference. Burt’s 1993 Matadors struggled to a 4-6 season and a last-place finish in the new conference. 1994 wasn’t much better, another last place and a 3-7 mark.

Following that season, a tearful Bob Burt resigned to take a high school job. He cited the stress of trying to run a Division I program on a shoestring, dealing with the referendum, and the lack of the administration’s emphasis on supporting football, with more resources going to other sports and a limitation on the number of players allowed on the football team. This was partially to comply with keeping equal numbers of male and female athletes based on the administration’s interpretation of Title IX provisions. Burt felt football was football, whether at a big-time program or a start-up small high school. He went on to coach successfully at the high school level, winning CIF-Southern Section championships. He was selected to the CIF-Southern Section Hall of Fame. In 2016, he was hired as Fallbrook High School’s head coach at age 74.

In 1995, Dave Baldwin took over as head coach and had just two wins, including a blowout over tiny D-III Menlo College. Apparently, the fired previous Athletic Director had to wait until the student referendum secured a continuance of football until he could firm up a schedule, requiring the opening game be against the Menlo Oaks. Baldwin’s gridders suffered eight, mostly lopsided defeats. The 1996 season was much better. The team took third in the D-1-AA Big Sky Conference behind second-ranked Montana and sixth-ranked Northern Arizona. The Matadors had a 7-4 season and beat two teams, ranking among the top 25 D-1-AA teams.

CSUN went 4-8 in 1997, crushing Boise State and Azusa-Pacific but having to forfeit both these games because two players were later discovered to have played despite being deemed ineligible because they had already played for two other universities, which was against NCAA rules. Under a new coach, Jim Fenwick, they finished second in the Big Sky.

In 1998 Ron Pociano took over the coaching duties, and the Matadors repeated a 7-4 season and second-place conference finish, beating two top 20 teams on the way.

In 1999, Jeff Kearin took over as coach. The team went 6-5 with a little help from a forfeit by Northern Arizona, who went on later to the first round of the D-IAA playoffs despite a last-place finish in the Big Sky Conference, yet a 16th rank overall nationally. With the millennium, Kearin’s fortunes fell, and the team finished 4-7. The following year was crucial for the survival of the program.

The 2001 season was mediocre. The team went 3-7, playing as a D-IAA independent. They had significant wins over Cal Poly and Western Oregon and a barnburner 49-36 win over Sacramento in their final home game in front of 5,286 fans. This was to be their last season playing football after forty years of competition.

President Jolene Koester met with the players and coaches three days after the final game. She announced that the program would be canceled due to budget issues. The athletic department was 750,000 dollars in the red, Governor Gray Davis was demanding the CSUN return a million and a half dollars back to the state, and future budget cuts were expected. The athletic director was required to submit a plan to reduce the deficit. He recommended dropping football, which costs over one million dollars a year, and coed swimming. Coach Kearin had plans to try to maintain the team, but they weren’t agreed to. It is just too easy to make up for past poor management and overspending by dropping the biggest and most expensive program, football. There were efforts to have another student referendum to raise funds to keep the program, but nothing came of the attempt, though the student body still favored keeping a team.

So, after forty years of competition, hundreds of students participating, thousands of fans attending games, some successes, and a respectable number of former players being drafted into the pros, Matador football is no more. There are a few wishful websites by students imagining what it would be like to bring back football, and there have been a few attempts to revive the program, but with no success thus far.

UC Riverside is one of six of the University of California system’s schools that have ever sponsored football. Today, only Davis, Berkeley, and UCLA have teams, and they are all D-I programs.

Riverside’s football history begins in 1955 under head coach Rod Franz, a college football hall of famer and two-time all-American guard at Cal. After graduating from high school in 1943, he served in the Air Force in the China-Burma-India Theater during the war. After the war, he joined other vets on the Bear’s football team as a starting guard. During his last three years, Berkeley had outstanding seasons, making the Rose Bowl in 1948 and 49. Franz was the team captain. Following graduation, he coached high school for three years, going undefeated his last two seasons at Diablo High, before going on to coach the Highlanders in their first season. The following year, he went on to an assistant coaching job for two years at Cal before focusing on a successful business career.

UCR’s initial season playing football was not much. They played only five games, tying Pomona-Claremont and losing to the La Verne College 40-0 and the Redlands Frosh Team by an identical score, before winning their first game in history against Cal Baptist, 36-7. Cal Baptist, a Riverside college, had played football in 1953 and 54 against junior colleges and JVs and began playing four-year schools in 1955 as an independent. They were winless in five attempts before meeting Riverside. Their program only lasted two more years. UCR’s final game was a loss to nearby Cal Poly, then at San Dimas, 21-13. Cal Poly, which had played football since 1947, competed primarily against junior colleges and small local colleges. They occasionally played service teams and even a prison.

Year two of Riverside football was under Coach Carl Selin. Their only win was again a 38-7 victory over Cal Baptist. In six losses, including against two JV teams, they only scored one touchdown and were outscored 251-44 for the season.

Things improved in 1957, but only slightly. Poor Cal Baptist fell to the Highlanders, 31-0, for the third and final time, as they canceled their program after the 1957 season. UCR lost the next four games against nearby small colleges and one small college in Salt Lake. They finished the season with a tie against the Chino Institute for Men, a state prison.

Cal Baptist started football in 1953, playing just two games, losing to the Chino Institute prison team 0-22 and Cal Poly Pomona 0-18. The Next year, they lost to Cal Poly again 0-32, but got a historic first touchdown and win against the 29 Palms Marines 6-0. In 1955, they began playing neighbor UC Riverside, along with Cal Poly Pomona, La Verne, and Long Beach State, losing all four games. In 1956, they continued cross-town contest with Riverside and nearby Cal Poly and La Verne, replacing Long Beach with Cal Tech, who clobbered them 67-0. A bright spot was a decisive win over a new Cal Western College team (USIU) 28-8, the Westerners’ only game. They lost again to Riverside in their only game in 1957. They took a break until 1961, when they played their final game against LA Pacific, losing 35-6, and called it quits for the final time.

LA Pacific combined with Azusa College in 1965 to form Azusa-Pacific. They had previously played each other three times and now were one, much stronger team. Both had played against Riverside.

The 1958 Riverside season opened against the prison with a 22-14 loss. The Highlanders tied the Pomona-Claremont Frosh squad 6-6 and followed up with a strong win over Cal Western of San Diego. Two more losses against varsity teams followed. Then another tie against the UC Davis Freshmen, 12-12, and a victory over the Long Beach State Frosh, 24-6.

In 1959, things really improved. The Highlanders played all but two of their games at home and mostly against varsity programs, going 5-2. Their only losses came against UC Santa Barbara’s JV and Western Arizona. New head coach Jim Whitney’s team outscored opponents 125-75.

The sixties began with a stunning improvement for Highlander football. They went undefeated against mostly varsity teams, also beating Chino Prison and a Navy Ordinance team. They even beat poor winless Cal Davis, whose football program started in 1915. They had one tie against Azusa and finished their first undefeated season with a 7-0-1 mark.

After such a stellar year, Riverside reverted back to a one-win season, only beating Cal Tech in 1961, going 1-7 against varsity teams and the El Toro Marines. The next season, they went 3-5, losing to first-year Valley State in their opening game at home by one point. In 1963 they played UC Santa Barbara for the first time, losing to Cactus Jack Curtis’s Gauchos 42-0 in Curtis’s first season at Santa Barbara. UCR’s only win came against Cal Lutheran after an opening loss, again, to Valley State. Of Riverside’s seven losses, all but one had negligible offense and no scores. They scored twelve points in their loss to La Verne, but the other six losses were goose eggs. They did manage a 14-14 tie against Pomona-Pitzer.

1964 brought in a new coach, Gil Allan, but not much improvement. UCR’s first of two wins were over Los Angeles Pacific in the opening game at home, 15-14. LA Pacific was a small Christian college that later merged with Azusa. The second victory was against Cal Tech, which was developing its winless reputation as a school full of brilliant engineering students but no superior athletes. The score was 13-0. Santa Barbara again took it to their fellow UC student-athletes, 48-7.

1965’s season began with a new coach, Pete Katella, and a string of victories, beginning with an opening win at home against the Davis Aggies, 16-14. The following week, they fell to a strong La Verne team but followed up with five straight victories before losing their last game 46-20 to Cal Lutheran. They finished the season 6-2, their best results since their undefeated 1960 season.

The 1966 season had mixed results, going 4-5 but winning all but one of their home games by substantial margins against nearby colleges. This continued during the 1967 season, which began with four straight losses by significant margins, followed by three strong wins, a tie with Azusa-Pacific, and finishing with a victory over a visiting Coast Guard Academy team. The season was 4-4-1.

In 1968 Katella turned the program around, producing a 7-1-1 season, playing only California colleges. The only loss came against CSU Hayward in their fourth season as a team. They tied Pomona-Pitzer 21-21.

In 1969, the Highlanders joined the CCAA, just playing one team in the conference during the season, Cal Poly Pomona, and losing 7-6. Of UCR’s six losses, two were by just one point, and one of their three wins, over Cal Western, was by one point. Katella left after a controversial year that included a player strike and complaints about the lack of university support for the program. UCSB had a similar strike by some of our new Black recruits the previous year. It seemed to be part of the zeitgeist during those times.

Gary Knecht took over the coaching duties in 1970, achieving only a 4-6 record in his first year at the helm. His second season went 2-7-1 with wins against San Diego University and Occidental and a tie with Whittier. They remained in the CCAA cellar for the third year.

1972 brought in a new coach, Wayne Howard, with winning ways. They went 9-1 and were co-champs with Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, which ranked number three nationally in the NCAA College Division. Howard had another great season in 1973, going 8-2 and taking second in the CCAA behind, again, Cal Poly, ranked eighth nationally, the only CCAA loss for UCR. UCR finished their season by crushing the US International Gulls (formerly Cal Western) 76-28, in UCR’s highest offensive showing.

Bob Toledo took over from Howard in 1974. Howard moved on to Long Beach and Utah, recording predominately winning seasons at both schools. Toledo continued the Highlanders’ winning ways by beating Cal Poly SLO, taking first in the CCAA, and going 8-3. USIU’s Gulls got a measure of revenge for last season’s debacle by beating the Highlanders 16-13 in San Diego.

1975 was an ironic season. Despite going 7-3 and winning the CCAA for the third time in four years, Toledo’s successful program was canceled by the administration, claiming a lack of fan attendance, though records show that in the last four years of the program, attendance ranged from a low of 1700 to a high of 4500 with most games watched by between 2000 and 3000 fans in UCR’s relatively small Highlander Stadium. The total attendance for the last four home games was 15,475, averaging 3,869 per game.

Chancellor Hinderaker announced he had decided to cancel the program due to “insufficient gate receipts.” The football program cost the university 165,000 dollars, with 125,000 for operating expenses and 40,000 for student grants in-aid for athletes. “Despite exciting and successful football teams the last four years and the NCAA Division II nationally leading passer and receiver this season, gate receipts contributed an insignificant amount to our football budget,” spoke the Chancellor as he brought down the hammer on UCR’s twenty-one years of college football. There are a few fantasy websites that imagine a future return of Highlander football to the big time in a fine stadium, but so far, this major university, like my own alma mater, has not returned to the gridiron.

San Francisco’s Best College Football Team: The ’51 Dons

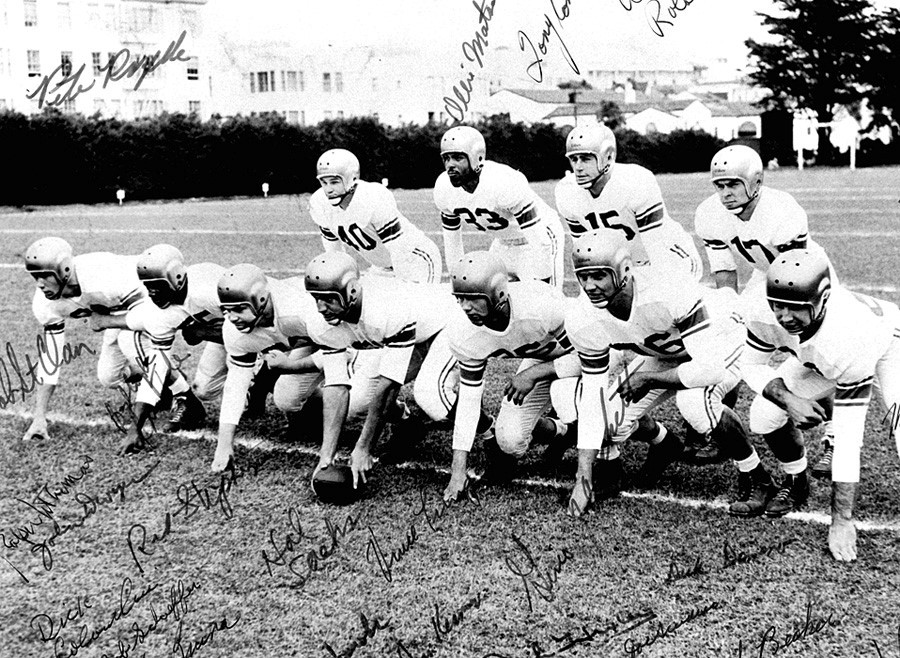

1951 Dons Football Team

Most of those who care, from the twenty-odd canceled college football programs in California, can boast of their institutions’ glory years. They are often forgotten, except for a few surviving alumni, old school newspapers, dusty trophy cases, and ancient Sports Hall of Fame lists. Each program had its successful coaches; some were legendary personalities, conference championships, outstanding seasons, bowl game appearances, high national ranking, and players who went on to pro careers. There are stories of amazing comebacks and upsets, exciting last-minute plays, huge crowds, and festive homecoming activities. These are largely unknown to current students, faculty, and administrators in the two-dozen colleges that abandoned football programs in our state.

Perhaps the most storied of the former California football teams is the 1951 University of San Francisco Dons. Like its neighboring Catholic universities, Santa Clara and St. Mary’s, USF once was a major football power. They haven’t had a team since 1982, and the more recent years were not all that stellar, but the university still remembers 1951.

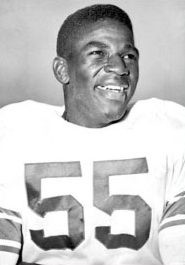

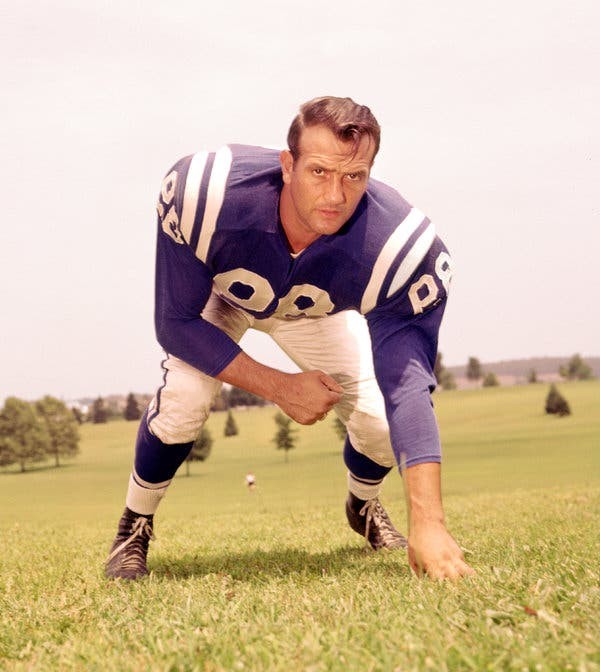

The 1951 team is remembered as the undefeated, untied, and uninvited squad. It was perhaps the best college football team in history. They went 9-0, had nine players drafted into the pros, three made the Hall of Fame, and five played in the Pro Bowl. Their coach went on to head coaching positions for Notre Dame and NFL teams, and their young sports information director, USF alum, Pete Rozelle, became the NFL commissioner in 1960, serving until 1989. He is remembered as the most powerful commissioner in professional sports. All this came from one team of about forty guys, mostly from the Bay Area and nearby Central Valley, in an all-male college of just 1,276 students.

The ‘51 team was the best of the independent college teams in the West and ranked fourteenth nationally among major football programs. But this is not why they are remembered today. The surviving teammates have been honored at bowl games, reunions, hall of fame dinners, and even in an ESPN documentary, “ ’51 Dons”, narrated by singer Johnny Mathis, friend to two of the star players. (Mathis sang at my aunt’s party in Ukiah when he was starting his career.)

Little known at the time, the reason the team is so famous today is for a game they didn’t play. Because of their success, it was hoped they would get an invite to one of the bowl games. The athletic department was deeply in debt. The 70,000 dollars that a bid to a bowl game would earn would shore up its expenses and highlight its program. At the time, the major bowl games were all in the South. The Orange Bowl committee sought a California team to play against an SEC team. USF was considered on their radar.

In mid-November the undefeated Dons traveled to Stockton to play the tough College of the Pacific Tigers, ranked as high as 16th in the nation earlier in their season. Eyes were on both teams for possible bowl bids. They played in what was eventually named Amos Alonzo Stagg Stadium for their longtime famous coach, who had retired only five years before. Stagg was known as the old man of football, an innovator inventing the man-in-motion play and the lateral. He is also known for establishing the first five-man basketball squads so his football players could play each other off-season to stay in shape. I played in that stadium when our UCSB Gaucho team traveled to play the Tigers my senior year. The stadium was demolished in 2012 and reemerged as the venue for women’s field hockey and a tennis complex. The University of the Pacific no longer fields a football team.

Tensions were high as the Dons entered the stadium in front of 41,600 fans. USF dominated the game, winning 47-14. The San Francisco fans, as was their habit during a season where the Dons crushed most teams by large margins, sang Huddie Leadbelly’s “Good Night Irene” as the game ended, rubbing it in to the dejected home fans. The Weavers’ version of the song had been number one on the top ten record charts for thirteen weeks in 1950 and came to symbolize a knock-out punch and also a lament over a profligate past. Ouch!

The Dons had to travel to Pasadena to meet Loyola College in the Rose Bowl Stadium the following week. A win might secure a bowl bid. They crushed the Lions 35-14. On the train going home, the coaches informed the team that the university had received calls from the Orange Bowl committee indicating they were being considered for the prestigious New Year’s game.

Imagine how this would have felt for players who had just completed a stunning undefeated season after hard months of grueling practice, under a coach known as “The Barracuda” for all the pain he put his players through. As one player recalled, he thought they were a track team because all they did was “run, run, run and hit, hit, hit.” The summer two-a-day practices were held in Corning, 170 miles north of cool, foggy San Francisco, in blistering heat. Players sought the minimal shade of telephone poles and sipped water from leaky pipes during practices. The effort paid off. Going to a top bowl game, which would also take the football program out of debt, was their hard-earned reward.

There was one caveat. The Orange Bowl was in Miami in segregated territory. No “Negro” players would be allowed to accompany the team. This was something the USF players could not understand. USF had integrated football teams since 1930. They played mostly Western and Northern teams and could not understand why their two star Black players would be banned from participation. It was all or none. They were as much a family as a team and voted unanimously to not accept a bowl bid unless all the players could go.

As guard Dick Columbi put it, “No, we’re not going to leave ‘em at home . . . we’re going to play with ‘em or not going to play.” Their season ended there, victorious beyond just the win, loss record.

Two days after the season ended, the university administration decided to cut their financial losses and drop the football program. A bowl bid would have saved it.

Though USF no longer supports a football team, the legacy of the ’51 Dons is an important part of the school’s identity.

Pacific did get a bowl bid as the second highest ranked independent team in the West, behind USF. They lost to Texas Tech, Border Conference champions, at the Sun Bowl in El Paso, 25-14.

The story of the ’51 Dons was the topic of Kristine Clark’s book Undefeated, Untied, Uninvited, published in 2002. She learned much about this team from Pete Rozelle and she also attended USF. She called the Orange Bowl administrators in an attempt to have the 1951 Dons players honored at the half-time of an Orange Bowl game. They knew nothing of the story and informed her there was no record of refusing to invite USF because of their two Black players. The 1951 committee invited number thirteen ranked Virginia, who refused to go because their administration wanted to avoid “big-time, subsidized football.” The game ended up between SEC co-champ Georgia Tech, number five, versus number nine, second-place Southwest Conference team Baylor. Tech won in the segregated contest.

The ’51 Dons finally did get to go to a bowl game. The surviving former players were honored at halftime during the 2008 Fiesta Bowl.

Who were these football heroes? They weren’t the first students to play for the University of San Francisco. The beginning of Dons football is recorded as 1917, when the Jesuit school was known as St. Ignatius Academy, and the team was called the Grey Fog. The school was founded as far back as 1855, long before football came into existence in anything like its current form. St. Ignatius eventually featured both high school and college level programs, suffering through the 1906 earthquake and fire and moving locations. In 1930, the name was changed to the University of San Francisco.

No team was fielded in 1918 during the war, as the small male college contributed members to the war effort. USF teams seemed to come and go. There were no teams on record from 1920 to 1923. The program returned in 1924, playing a mix of clubs, colleges, and military teams. In 1927, the Grey Fog Eleven began a long-term series with local Catholic college rivals Santa Clara and St. Mary’s. The series stopped for a while during WWII, then resumed until football was dropped after the fantastic but fatal 1951 season. USF also began competition against other Catholic colleges, including Loyola of Los Angeles and Gonzaga of Spokane. Home games eventually were played in Kezar Stadium, later home to the 49ers pro team. Crowds could be large when local rivals St. Mary’s or Santa Clara were opponents.

The 1930s was a rough one for the US economy but generally a respectable one for both the newly minted University of San Francisco Grey Fog football teams and for a moral stance taken by the administration. In 1930 USF welcomed African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and new immigrants to their campus. USF was one of the first universities to integrate its football teams in the nation. Starting tackle Isiah Fletcher was the first Black player for the Grey Fog.

The 1930 season had a respectable 6-3 winning record, playing a mix of their Catholic rivals, military teams, the University of Nevada, and the famous Olympic Club of San Francisco.

In 1931, they compiled a 4-4-1 record, adding BYU to their schedule and traveling to play the University of Hawaii Rainbow Warriors in Honolulu Stadium. (I traveled with the Gauchos in 1967 to play on a muddy Honolulu Stadium field in front of a huge local crowd there for a game honoring the local American Legion organizations. We lost to the Warriors but had a wonderful time in Hawaii. Maybe that is why we lost.) The old stadium, known as Termite Palace, was torn down in 1974 and was replaced with Aloha Stadium. The old site is now a public park. The USF season included the usual college rivals, plus the Olympic Club and the West Coast Army team, tying both.

Things went downhill in 1932 as the Great Depression loomed over the nation. They played all their games but one in Kesar, finally beating the Olympic Club and traveling down to play Loyola in Wrigley Field, a minor league baseball venue. They won that game handily but lost to their local rivals, Santa Clara and St. Mary’s. They lost to a tough Stanford Indians squad in their opening game.

As the Depression continued, so did the fate of the 1933 team. They had just one win against Gonzaga and tied Loyola in a scoreless contest. All the games except one were at Kezar and that game was played in the Seals minor league baseball stadium. (I attended my first pro baseball game as a kid, watching the Seals play in that stadium. The Giants were still in Brooklyn.) Most of their games were close contests, including their games against Stanford and Oregon. It was their lowest ranking ever as Western Independents.

Things picked up gradually during the 1934 season. They traveled to Corvallis for their opening game and beat Oregon State 10-0. They lost to Santa Clara and Stanford in close contests. The total points scored for and against during all the season games, except Gonzaga, equaled only 16 for vs. 16 against. They traveled to play Loyola, and 10,000 packed the small stadium to watch the two teams battle their second consecutive scoreless game. It must have been a very defense-oriented season in California football. The Grey Fog did run up the score, 28-0 against Gonzaga. Perhaps Gonzaga didn’t get the message that tough defense was expected this season. The season ended with a 7-3 loss to Santa Clara in front of 45,000 at Kezar.

The 1935 season was the first winning season since 1930 at 5-3, only losing to tough local teams, including Stanford, in front of large crowds. They added Denver and Fresno to their schedule, dropping any non-collegiate teams while continuing to play Nevada and their Catholic rivals.

In 1936, the Grey Fogs returned to mediocrity. They traveled to San Antonio to tie Texas’ St. Mary’s 6-6 and later tying California’s St. Mary’s in another defensive standoff, 0-0 in front of 35,000 fans who hopefully enjoyed watching defensive play or maybe the school bands. USF added Montana, Portland, and San Jose to their schedule, going 4-4-2.

They opened the 1937 season hosting two Texas teams, St. Mary’s, with 20,000 attending, and tiny Daniel Baker, a college that eventually went bankrupt. That game only drew 2500 to the same Kezar stands. Huge crowds attended the St. Mary’s and Santa Clara games; 55,000 crammed Kezar to watch the Gaels-Dons game. It was another so-so 4-5-1 season, though they added Texas A and M and Michigan State to their schedule.

Back to the winning column in 1938, at 5-2-1, but losing to their local rivals back-to-back. All their first six games were all in San Francisco at either Kezar or Seals Stadiums. They won both their road trip games against Fresno and Gonzaga. They hosted another Texas team, Harden-Simmons. They played my Gauchos at Kezar for the first time, beating what was then Santa Barbara State 14-0.

Things began to slip again as the nation moved toward WWII, with a 4-3-3 1939 record. Ties were common, including a rousing 0-0 tie in La Playa Stadium, Santa Barbara, where I played 27 years later. They also tied Santa Clara when the Broncos were ranked 14th nationally. They added a Missouri Valley Conference team, Creighton, to their schedule. Seems like out-of-state teams jumped at a chance to travel to San Francisco for a game. Good for recruiting.

Nineteen-forty was a sad year. Their only win came against Loyola, but they managed another 0-0 tie with Creighton and lost a very close game against number eighteen Texas Tech in early December at Kezar.

A new coach took over in 1941, and things improved. They went 6-4 and were the third-best team among the Western Independents behind Hawaii and Santa Clara. They began to score offensively and avoided those 0-0 ties. This season they played a military team for the first time in years, Fort Ord. Their last game was a loss to Mississippi State at Kezar on December 6th, as Yamamoto’s forces advanced on Pearl Harbor.

In nineteen-forty-two, they continued playing during wartime, adding two military teams to their schedule. They lost to all three California Catholic colleges and to number sixteen Mississippi State but crushed Arizona State 54-6. The Dons ranked third among Western Independents behind number seventeen Santa Clara and St. Mary’s. They were again under another first-year head coach.